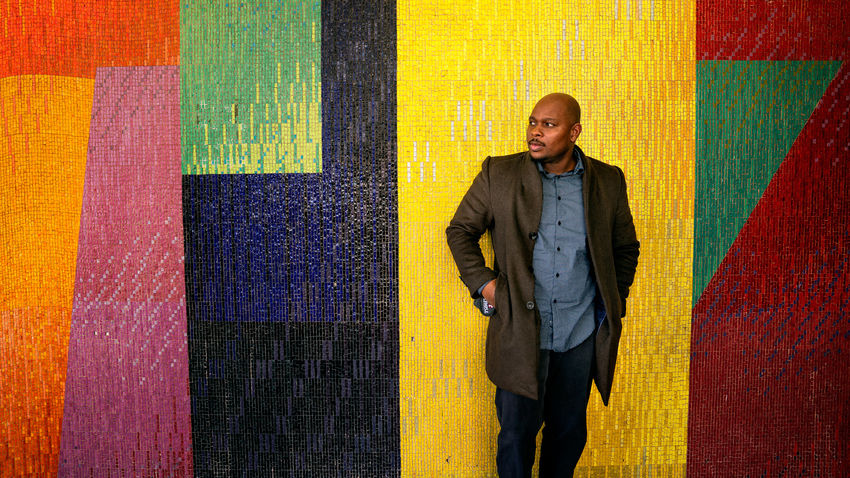

When Sheku Sillah started his nursing career, he always hoped to one day return to his home country of Sierra Leone, which—when he left the country at the age of 10—had an average life expectancy around 35. As a doctor of nursing practice student, Sillah fulfilled that dream, traveling to Freetown, Sierra Leone, on a trip to deliver medical supplies and evaluate the state of healthcare in the West African country. Since then, he has returned on multiple occasions alongside other Temple students.

What first brought you to Philadelphia?

I was born in Sierra Leone. My father was already living here in the United States, but my parents wanted me to get a basic education in Sierra Leone before we’d come here, in order to learn in our own culture. But then civil war broke out in 1991, and when it reached our city in 1997 we needed to leave—they were killing people, and there were rebels everywhere. So we went to Guinea, and my dad met us there and brought us to the United States. I’ve been living in Philadelphia ever since.

How did you become interested in nursing?

My older brother is a nurse and has always been a good mentor for me, so he is one of the reasons. We always wanted to do something in healthcare, because the system where we’re from is one of the worst in the world. When you see what you left behind, you want to gain enough education to go back and help.

I see how healthcare facilities in the U.S. compare to third-world or developing countries, and there are so many disparities; but, then again, healthcare providers here can also learn from those situations. I would like to help bring students from the U.S. to see healthcare systems in those other countries and gain a different perspective on healthcare, to see something that’s not within the norms of what they see here.

How has your experience been so far?

Temple’s DNP program has been really great so far. They work so closely with underserved communities in Philadelphia, and that aligns closely with what I would like to pursue once I graduate. The neighborhood we’re in—it’s very much an impoverished neighborhood. So, I enjoy being at a place like Temple, where you are doing everything you can to help push back against this healthcare disparity.

Where do you envision yourself after you complete your degree?

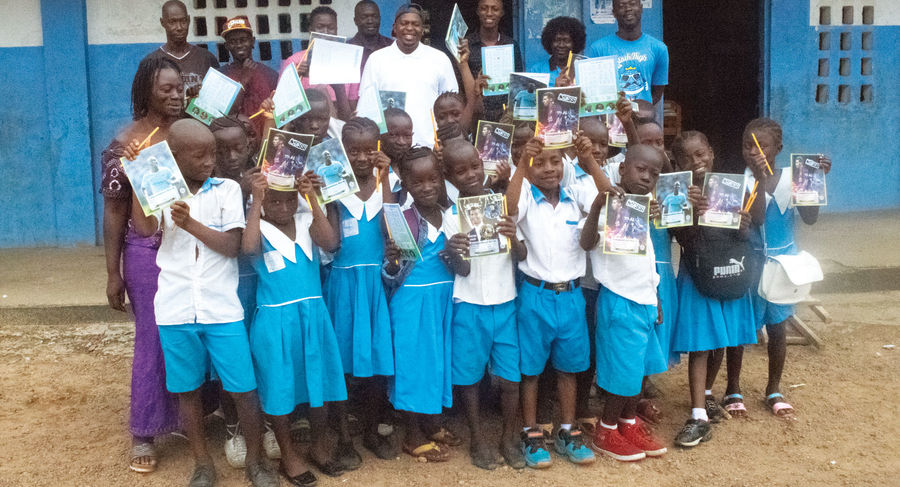

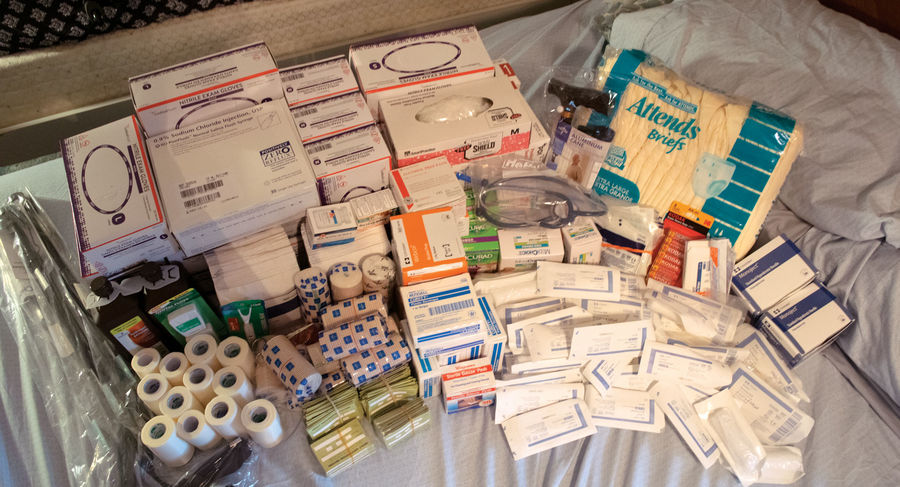

At first, I would like to stay in the U.S., working in an underserved community and mastering my field. But eventually, I want to do something internationally. I’ve been doing a lot of international work now, as a student. I’ve been going back to Sierra Leone; I collect books and medical equipment from hospitals and coworkers and we go back and donate to hospitals, nursing schools and medical schools over there.

What did you learn from that trip? What are some of the challenges facing Sierra Leone?

I’ve seen some of the most devastating things that you can see, as far as lack of resources. As a nurse, you are aware of all the resources that you have: you know what you have in your facility and you know what you need. And when you go somewhere that doesn’t have these things, you immediately notice it.

I’ll give you an example. We went to a facility in Sierra Leone, and the head nurse told us she has one stethoscope, one blood pressure machine, and she takes it from unit to unit to check patients’ blood pressure. You would never do that here, because cross-contamination is a major issue.

There are things that, when you see them, you’re immediately aware that they in no way should be accepted. Healthcare—and I mean just a basic form of healthcare—should be a human right.

I’ll continue to do what I can in my own small part to make whatever difference I can make, and hopefully somebody else will pick it up, keep the ball rolling, and eventually the playing field will be more level. I think that if the younger people over there can get the opportunity that we have here—if they have the opportunity to become doctors, to become engineers, to make the changes needed—I think they’ll have the ability to compete on the world stage.