Between municipal regulations, city ordinances, and state and federal laws, there are a lot of rules for disaster responders to keep in mind. Given the hands-on and immediate nature of their work, they can face harassment, legal issues, and a wide range of licensure requirements—and understanding the nuance of these rules can be exhausting, taking time and energy away from the important work of actually responding to emergencies. Often, it’s hard to even know what these laws are, leaving responders to deal with diving deep into government websites and endlessly parsing documents.

But thanks to the Emergency Law Inventory (ELI) developed by a team led by Elizabeth Van Nostrand, associate professor of health services administration and policy, navigating this legal labyrinth is that much easier.

“Before we began working on ELI, we knew that an unfamiliarity with the laws was a barrier to participating as a disaster responder,” said Van Nostrand, who describes herself as a “late academic,” having spent the first part of her career as a litigation attorney before working in emergency preparedness law at the University of Pittsburgh.

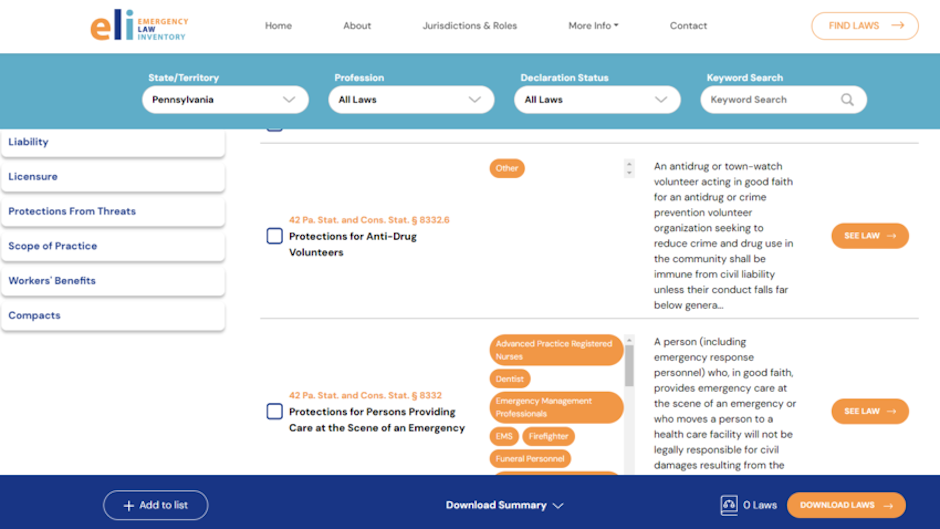

With more than 1,800 laws logged across the 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.; eight territories and freely associated states; and the federal government, ELI compiles statutes, regulations, and compacts in five major areas: licensure, workers’ benefits, liability, scope of practice, and protections from threats. Laws pertain to a variety of roles, from physicians and emergency medical services personnel to firefighters, social workers, and even private property owners—anyone who may be involved in responding to disasters.

Funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), the process of building the system was a large task led by a small team: just Van Nostrand, two JD/MPH students, and an evaluator from the University of Pittsburgh (where Van Nostrand worked at the time) poured over countless web pages to identify, compile, and summarize 1,500 laws in just 18 months.

To help guide the project, they partnered with the Medical Reserve Corps in Allegheny County and rural Ohio, as well as the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and boots-on-the-ground responders.

The first iteration launched in 2017 with 1,500 laws and four areas of focus. Now, with additional funding from the CDC, Van Nostrand and her team have launched a retooled and expanded ELI at Temple that covers an additional legal area, offers more user-friendly options to search by keyword and build an exportable list of laws, and provides supplemental resources that help responders navigate regulations for specific organizations and laws that pertain to different types of emergency declarations.

They also reviewed each of the existing laws and updated or added to the inventory when necessary—though this time, they had additional help in the form of a research project manager, volunteer attorneys, Temple’s Center for Public Health Law Research, and law students from Temple, the University of Pittsburgh, and Villanova.

“The reception to both iterations of ELI has been overwhelmingly positive,” said Van Nostrand.

“Even after we quit promoting it, the numbers kept rising. In any given month, we’d have something like 400+ new users,” she said. The project also received the National Partner Award from the National Medical Reserve Corps. “It's extremely rewarding as a researcher to have ELI being used by so many people and being told over and over again that it's really helping the people who help us.”

For now, the team is finishing up some of the few remaining features and working on dissemination. But Van Nostrand doesn’t expect that this is the end of the work on ELI—or the methodology behind it.

“I would love to see the methods we’ve used to code and sort these laws applied to a different area of law,” she said. “There’s no reason why this methodology and filtering system couldn’t be applied to laws pertaining to healthcare privacy, or labor laws, or telehealth law.”