Sarah Bauerle Bass will use a new collaborative grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to expand a software tool she developed with Michael Hall, an oncologist and clinical cancer geneticist at Fox Chase Cancer Center, to help cancer patients make informed decisions about their care. Bass and Hall created Gene Pilot, a user-friendly online application that explains the potentially useful procedure of tumor genetic profiling (TGP) and helps patients articulate their questions and concerns about it.

The use of multi-gene TGP to examine a patient’s tumor for targetable mutations can personalize cancer treatment to individuals and improve survival rates. But the procedure can also identify secondary hereditary risks that could have implications for the patient and their family. It is underutilized in certain populations, due to a range of patient concerns, including mistrust of the medical system. Bass directs the Risk Communication Laboratory at Temple’s College of Public Health, studying how public health messages can be crafted for diverse audiences to enhance health decision-making. The initial version of Gene Pilot, created with funding from the American Cancer Society, is built based on focus groups and surveys primarily to address the concerns of Black cancer patients. It’s currently in trials at Temple University Hospital (TUH) and Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Under the new grant, Bass, along with co-PIs Hall and Tracey Revenson, a professor of psychology at Hunter College, will create a version of Gene Pilot for Latinx patients. The funding represents a renewal of a prior five-year grant that created a cooperative cancer research center called Synergistic Partnership for Enhancing Equity in Cancer Health (SPEECH) (U54 CA221704(5)-6), directed by Grace Ma, associate dean for health disparities at Temple’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Camille Ragin, professor of cancer prevention and control at Fox Chase; and Joel Erblich, a behavioral health scientist at Hunter.

“There is a huge disparity in both cancer treatment and mortality rates in cancer for Black and Hispanic cancer patients,” Bass explains. “They get diagnosed much later, so they’re much more likely to be diagnosed in stage three or four. They're less likely to participate in clinical trials that may give them access to new treatments. And they have much higher mortality rates. There's a whole array of social determinants that cause this to happen.”

Many concerns that patients may have about genetic testing are universal, Bass says. But there are cultural variations, and understanding those variations can help all patients feel more confident in making treatment decisions. Patients may be concerned about issues including the accuracy of genetic tests, about who will have access to information from the testing and how it may be used, and about the impact that genetic findings may have on their insurance coverage or their family dynamics.

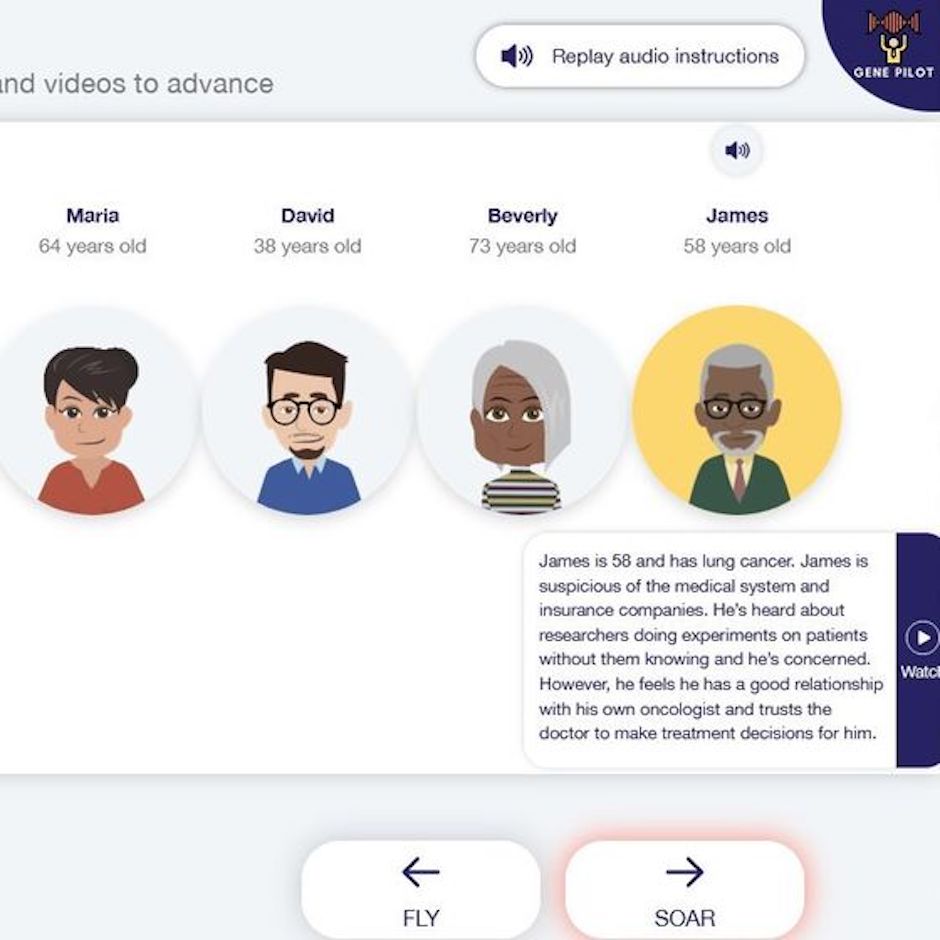

Gene Pilot uses interactive text, audio, animations and video to explain TGP and give voice to issues patients might be considering. An animation explaining the testing says: “Targeted therapy is an important way to treat your cancer, and it starts with a TGP test. This test is looking for unique changes in the genes of your tumor so that a drug treatment could be made specifically for you. They take a piece of your tumor and look at the DNA, the instructions that are in the genes. This information then lets your doctor understand if there are certain treatments that will better treat your cancer. This all sounds great, right? But there are some issues that you should know about.”

An animated vignette about a hypothetical patient named James says: “Not trusting the medical system or medical research is an important consideration for some patients. They may be worried that researchers would do experiments without them knowing or don’t believe that doctors give them all the information they might need to make decisions. This is understandable, especially for those who have had negative experiences in the past. James feels that minorities are discriminated against in research but he also feels he has a good relationship with his oncologist and trusts his doctor to make good treatment decisions about his cancer.”

A section at the end of the Gene Pilot program helps patients indicate their own concerns and formulates questions they can bring to healthcare providers.

“The tool tries to provide talking points about what's most important to patients, so they can be really concrete in talking to a doctor,” Bass says.

The new phase of development for the decision-support software will add Spanish-language narration and examples and incorporate findings from focus groups and surveys that have been conducted among Latinx cancer patients under a pilot project funded by the first five years of the U54 Center. Trials of the modified software will be conducted for English- and Spanish-speaking Latinx cancer patients at TUH, Fox Chase, Cooper and Columbia University hospitals.

This project was supported by the TUFCCC/HC Regional Comprehensive Cancer Health Disparity Partnership, Award Number U54 CA221704(5)-6 from the National Cancer Institute of National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH).